Byzantine discussions on the decolonisation of development cooperation

Taking advantage of the time while I work in the garden, I have been listening to the podcast Living Decoloniality to improve my training in what seems to be the fashionable topic. It is a very well done and interesting podcast; however, I didn’t find anything that wasn’t already being talked about in the 1990s: listening (except that now it is active), participation (although back then it wasn’t said stakeholders), local decision-making, etc.

Driven by curiosity, I searched Google Scholar to see how many articles have been written on decoloniality since 2019. Starting at just over two thousand, around 1,500 articles per year have been added to reach seven thousand publications in 2023 alone. I am concerned about this trend.

I think there are three important reasons why we as a cooperation sector are spending more time than necessary discussing decolonisation, although this does not mean that the topic should be silenced.

I will not dwell on the first one, because I already spoke about it in another article, where I said that there is not much chance of changing the way donors act, because they have the money and they want it to be justified on their terms.

The second reason is that there is a deficit of doing things. I am an aid boomer, who in the 1990s worked listening to Quilapayún and Mercedes Sosa: to build this wall, bring me all the hands: the blacks, their black hands, the whites, their white hands.

Today things have changed and due to the prevailing climate, the whites don’t quite know what to do with their white hands. In recent years, I have witnessed Northern NGOs downsizing at a faster rate than Southern NGOs have been able to cope with in order to continue to do the work that used to be done between the two. Among the issues most affected by this shortfall are writing new projects and improving accounting control. As a result, colleagues in the sector have confirmed to me that project funding has decreased. The latter partly because not enough projects are being written, and partly because the quality control of those that are implemented has declined, much to the chagrin of donors. White hands have been withdrawn too quickly.

One solution to this problem would be for Northern NGOs to engage in advocacy rather than implementing projects in the South, but their legitimacy is also determined by the things they do as well as the things they say. If they do less and less, there will be fewer and fewer staff, and fewer and fewer things will be done, until they do nothing and disappear as irrelevant. This would not be a bad outcome if it happened because all the work has been taken over from the countries of the South. But this is not the case.

The third issue is that spending too much time talking about one issue takes time away from talking about others. These are the ones I mention in the previous paragraphs, for a start, but also the erosion of funding for NGOs in the North, for two reasons.

First, because governments have become right-wing (see this article from the Global Development Centre). The UK, Germany, Sweden and Norway have all made large cuts in their aid budgets.

The second reason is that the donor base of NGOs has shrunk: in Spain it is steadily ageing, with a current average age of 59 years and 61% of members over 55 years old. Young people are no longer motivated to fund NGOs because their way of getting information has changed. It is now through social networks, where gym cryptobros send unsupportive messages. More right-wing young people are less interested in cooperation (if not radically opposed).

For NGOs, obtaining their own discretionary funds – which they can use freely – is increasingly difficult. It is this funding that makes it possible to improve participation prior to the start of projects, because this costs money: project development needs to be planned in advance, meetings need to be held with communities, projects need to be written slowly. Donors do not usually pay these costs.

This is not to say that decolonisation should not be discussed, nor that participation, inclusion, power-sharing and a feminist approach should not be discussed or ignored. But there are existential problems that should also be prioritised. NGOs, North and South, should be machines for designing projects, investing funds well and justifying them better, as long as governments do not take poverty into their own hands.

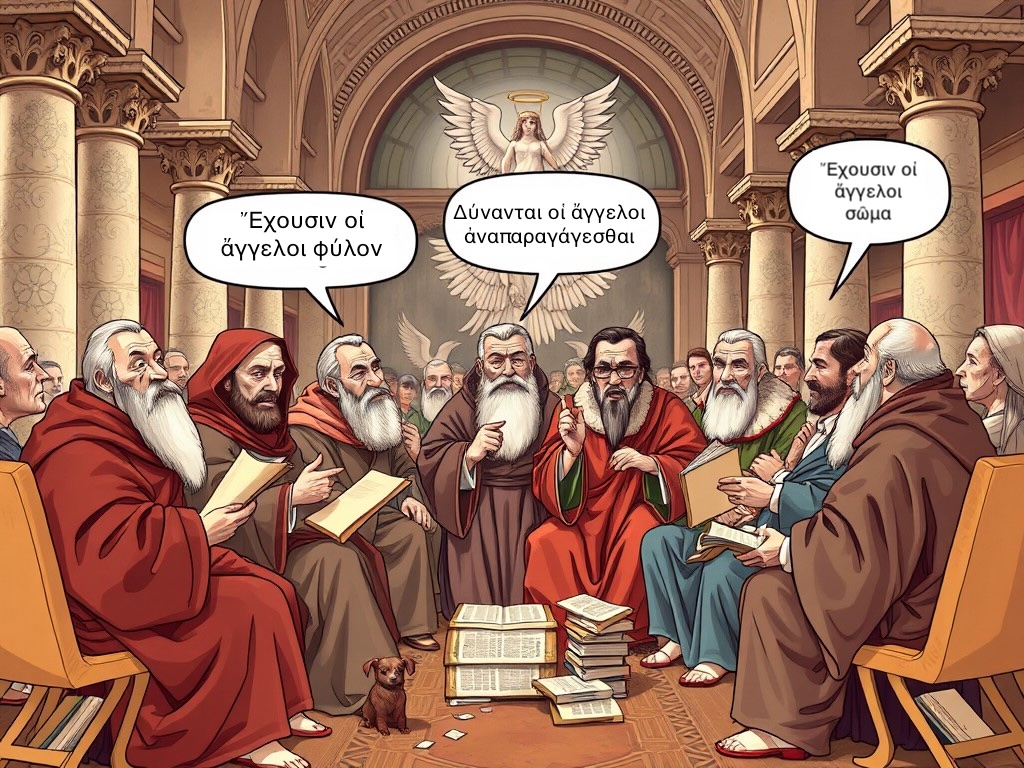

The talk of decolonisation in the aid sector, both North and South, reminds me of the fall of Byzantium, where the hot topic was the sex of angels. This disconnection with reality led them to neglect a more important issue, the defence of their territory against Ottoman invasion. The Byzantine empire was extinguished without giving them time to finish the discussion.

Post a comment