How People Think about the Economy

With my pre-retirement, this blog is changing topics. From now on, my intention is to understand the world better. I have a reading plan prepared, and I will be posting summaries of what I am learning. We start with economics and evolutionary psychology.

We normally assume that the concepts of economics held by the common people – I mean people with a medium to low level of education – deviate from academic economics due to ignorance or the use of fallacies to draw conclusions. According to Pascal Boyer, an anthropologist, and Michael Bang Petersen, a political scientist (and both evolutionary psychologists), this is not the case. They explain this in the article How People Think about the Economy.

The reason why popular beliefs do not coincide with academic beliefs is because our brains use unconscious deduction processes that have been formed during the evolution of our species. These explicit beliefs also influence political choices, which explains (and these are my words, not Boyer’s and Petersen’s) why there are red-neck fascists, poor people who vote for political systems that harm them, and the rise across Europe of the redbrowns, a branch of fascism that mixes xenophobia with apparently left-wing demands.

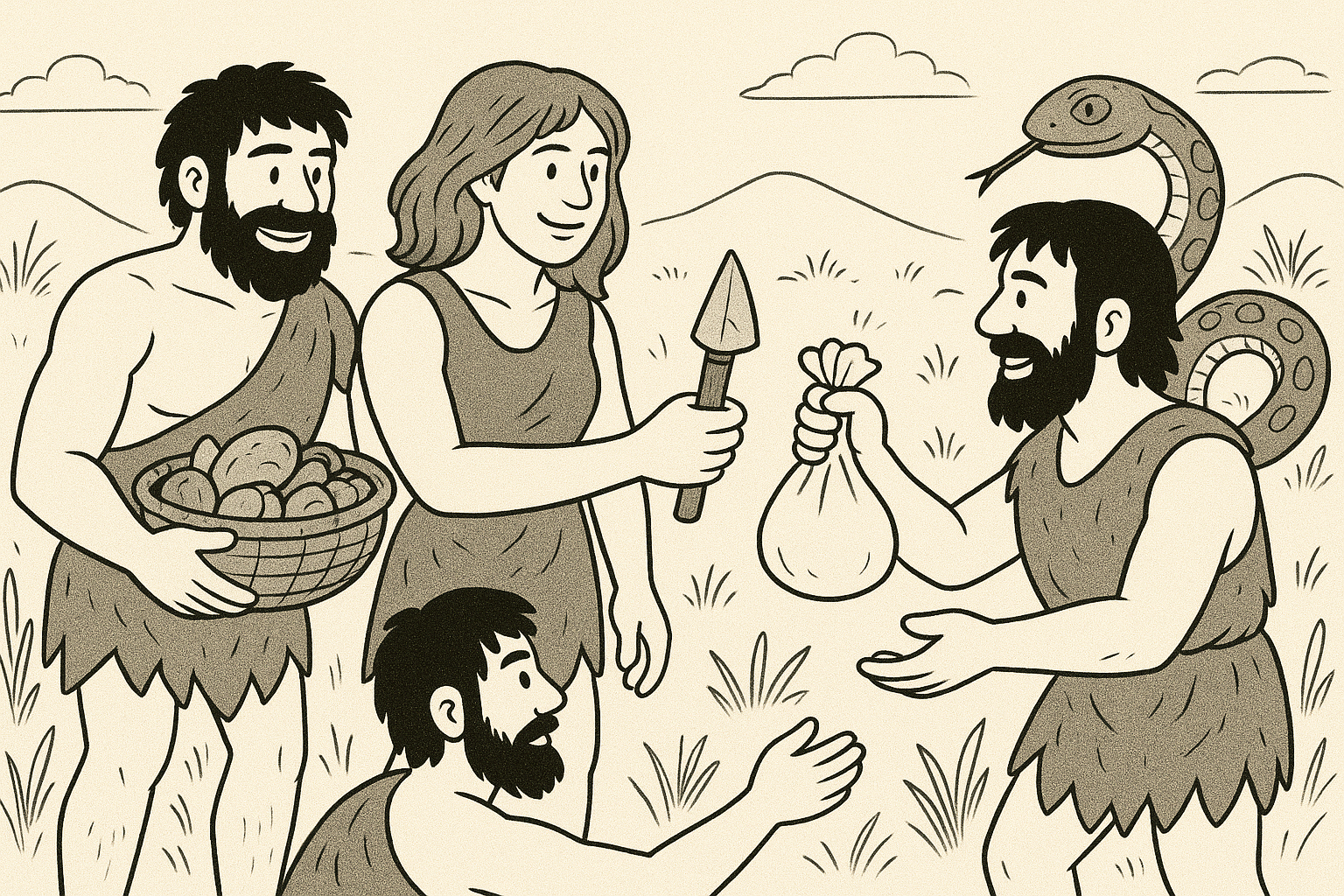

These unconscious deduction processes originated to solve adaptive problems we faced hundreds of thousands of years ago: 1) what an exchange of goods (food, tools) has to look like to be fair, 2) who you can reliably exchange goods with, 3) who to join with to achieve your goals (coalitions), and 4) what is yours, and what belongs to the group. These four problems shape our intuition about the modern economy, but they originated in small groups of less than a hundred people.

This is not an explanation of how things should be, it is a description of how they are. Nor does it imply that beliefs lead to better or worse outcomes, or for which groups. It is a finding that normal people do not think like economists.

What examples do Boyer and Petersen give of this kind of intuition?

- International trade is bad, because it is a zero-sum game. What we don’t produce at home is of no benefit to us.

- Immigrants steal our labour because the labour pie to be shared has a fixed size.

- Immigrants take advantage of our social services because they do not deserve to receive social benefits if they do not contribute (contradictory to the previous one, but it is important to know that popular beliefs in economics can be contradictory to each other without creating problems for the believer).

- Social services are also used by vagrants and lazy people. Interestingly, this belief varies depending on whether you know the person receiving the benefit.

- Markets produce bad outcomes for most participants. The market is not seen as a place where goods are exchanged, but as a struggle between actors with very different strengths.

- Having economic profit as a motivation is bad for the general welfare.

- Labour is the real source of value, i.e. the value of a good is measured by how much labour has been applied.

- Price regulation works (whether of rents or wages).

Many of these intuitions can be found on the far right as well as on the left, and the fact that they are widely and repeatedly produced explains their intuitive origin. In Boyer and Petersen’s article you can see which studies support each case. They are automatic, unconscious mechanisms that produce results that do not include an explanation of the steps that have led to such a conclusion.

This does not mean that these intuitions are not reflected upon and more elaborate thoughts are not produced, qualifying or explaining the intuitions. Popular economic beliefs are the result of these reflections, which take into account the economic information to which one has access, and the basic intuitions mentioned above. Contradictions may arise, but the lack of detail in the explanation allows for them.

They are cultural beliefs, which means that they are shared by many people and transmitted by sharing ideas. They evolved when there was no modern means of communication, when we didn’t live in cities and knew the members of our group. It allowed us to detect free-riders, and to know who to trust in exchanges.

This, and these conclusions are my own, explains some things that have happened in recent years: why has Trumpism become anti-trade? Because they have seen that their voter base could grow enormously. Before, the right was pro-free trade, and it was harder to sell this idea to the poor. Why the intense anti-immigration propaganda? For the same reasons. Even anti-elitism (the wonder of making the Trumpist grassroots believe that they are against the millionaire elites, an idea promoted by the richest man in the world) has been done by exploiting the fact that this idea rests on a basic intuition embedded in our paleolithic brain. Social networks have done the rest.

The article is worth a read, is part of a book with other interesting articles, and can be downloaded for free and legally from here:

https://www.openbookpublishers.com/books/10.11647/obp.0257

Post a comment