The debate on food reserves is back

During the two food price crises between 2008 and 2012, there was an intense academic and political debate on whether or not to create food reserves.

In terms of the diagnosis of the problem, there was much talk about biofuel production, which had contributed to the shortage of grain reserves, some of which were used to produce alcohol. But there was no consensus on the degree of importance. There was consensus that the low level of commercial stocks (the so-called stock-to-use ratio) was a triggering factor.

One of the most intense debates was about the effects of financial instruments such as futures markets on the crisis, with some saying they were pernicious and others that they were necessary. One widely shared conclusion recalled a famous Galician expression: “I don’t believe in witches, but they do exist”. It could not be proved that futures markets increased prices too much, but they did increase them.

On solutions, there were also varied positions. The possibility or not of maintaining an international reserve was discussed, but with some misgivings about its effectiveness. Regional and national reserves were proposed, as well as stopping biofuel production in times of shortages (this would work, but needs coordination). This open access book summarises many of the proposals.

As is often the case, once the crisis was over, the debate was over, and there was not much more talk about the issue. Then came COVID and the price spike in the wake of the Ukraine crisis, but the subject remained untouched. Until now.

Isabella Weber and Merle Schulken have produced one of the most comprehensive analyses of the need for food reserves in a paper. Not only does it go further back in time, revisiting the views of classical economists, but it updates the causes of food price crises and adds concepts such as “sellers inflation“, a concept that Dr. Weber has developed. In short, that companies with market power have the ability to raise prices when they want to, something that may seem obvious to most of us, but was difficult to prove with figures.

His approach to food stocks is that the neoliberal approach has left global economies ill-equipped to cope with the influence of shocks from war, climate change and pandemics on staple food prices. Current emergencies revalidate the classic argument for the need for global reserves, because uncertainty and pro-cyclical behaviour can render commodity markets inefficient. Price volatility can cause inflation and low growth and sends the wrong signals to the market, which is not always able to recover equilibrium.

Price stabilisation through food reserves would benefit macroeconomics and development in countries dependent on both food commodity exports and imports. Weber and Schulken propose the creation of specific institutions for emergency price stabilisation tailored to each sector. The idea would be to move away from the world of perfect market competition, which does not exist, to institutions in charge of price stabilisation.

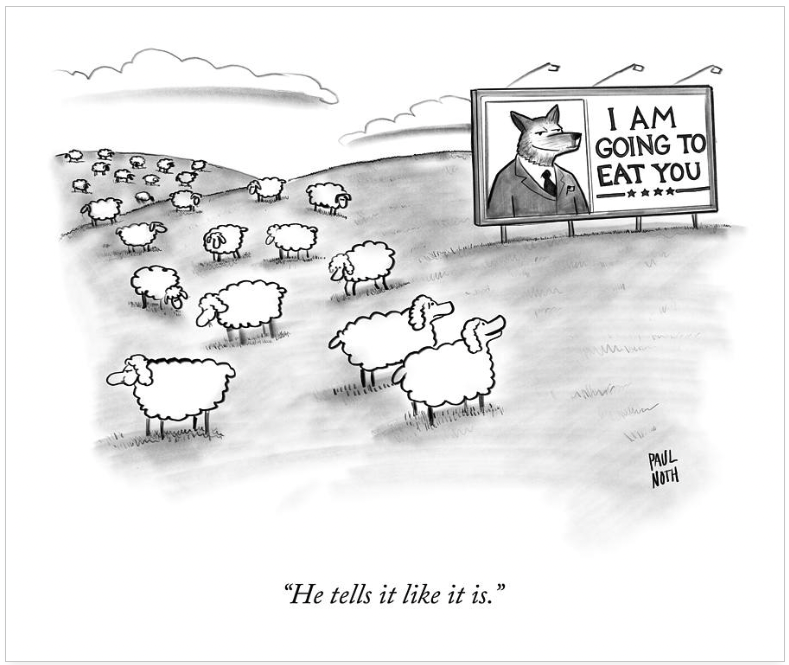

This paper is welcome above all for reopening a debate on how we prepare for the crises to come, and among them, above all climate change. The existence of good, intelligent and necessary proposals does not guarantee their adoption, however, in a world dominated by the interests of large multinationals such as the famous ABCDs, which earn billions of dollars at each price spike.

Apart from giving visibility to the issue of reserves and trying to influence what the money for climate change adaptation will be spent on, where do I see the need for a more detailed proposal going forward?

First, the necessary size of the reserve should be defined. A 2016 proposal talked about 500,000 mt. Its objective was to deal with emergencies and not to stabilise prices, which would require a much larger size, but what this would be remains to be discussed.

The second point would be the location. The paper says that the location would have to be “global”, but it will have to be specified in which countries it would be efficient and logistically acceptable to importers and exporters. The new global disorder in which we find ourselves seems to be leading to less cooperation between countries, not more. This is not a hopeful situation.

Another point to be resolved is the modality of intervention: Priority access for countries with high import dependence? To those that have problems with access to foreign exchange to pay for imports? How to prevent adverse effects on markets, which are inevitable, when grain has to be sold to replenish stocks? Several options were aimed at converting surpluses into alcohol, to avoid flooding neighbouring countries with grain that is too cheap. This proposal makes a lot of sense.

And finally, it should be borne in mind that stabilisation has to protect not only against high prices, but also against low prices, which are just as often a problem, if not more so, and which hurt farmers. Public purchases of grain from agricultural cooperatives are a way of favouring small producers, already successfully tested in the West Africa Regional Food Security Reserve. AECID (the Spanish agency for developmetn cooperation) has supported this project without interruption since 2013, and has many lessons to show on how regional reserves, national reserves and local cooperatives can be linked.

The ideas are there, only the decisions are missing. Whatever solution is applied, it is clear that there needs to be a clear relationship between the size of the problem in the event of a new food crisis, and the resources devoted to mitigating it. As a wise, albeit anti-ecological, Central American saying goes: the size of the stone matches the toad.

Post a comment