How to fix the food system in simple steps, or not

Agriculture is responsible for a quarter of climate change. On top of that, the food system has shown its fragility with the war in Ukraine, which has led to unprecedented price hikes that may be worse than the 2008-2012 food crisis. This is due to a combination of rising gas prices, fertiliser shortages and the lack of international access to Russian and Ukrainian grain.

Is it possible to build a food system that can withstand these two challenges – carbon footprint and stability – but does not consist of simple solutions to complex problems?

Among the ideological sectors – I am not talking about the scientists – most concerned with mitigating climate change, similar recipes are often proposed, which end up being worse than the disease due to certain biases that are common on both sides of the ideological spectrum. One of these biases is that we listen to the experts who agree with our ideas, and tend to ignore those who do not. We believe the experts when they tell us that climate change has human causes, but we don’t believe them when they tell us that the solutions we propose to solve it don’t work.

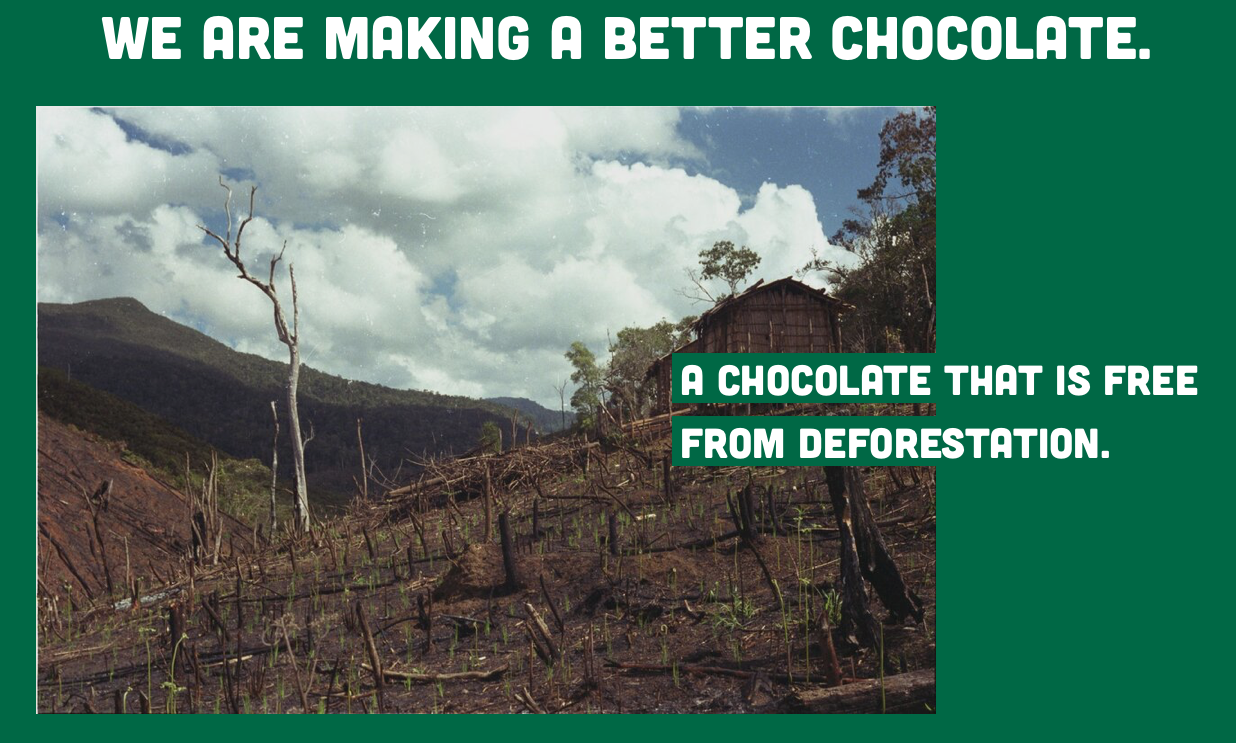

When we propose agroecology to reduce the carbon footprint, we do not take into account that its yields are lower compared to conventional agriculture. Lower yields mean more land is needed to produce the same amount of food, which in turn means more deforestation.

But the agroecological world is resistant to evidence and its consequences. When Sri Lanka’s president decided a year ago to ban the import of fertilisers and pesticides, it seemed like a great idea at the time. A year later, at least part of the crowd besieging the presidential palace these days is made up of angry farmers. The country is facing a brutal decline in yields, which has meant a drop in tea exports that has cost the country $425 million, and a 20 per cent deficit in rice production, when it had always been self-sufficient.

What if instead of taking a year to reduce chemical fertilisers, Sri Lanka had taken ten? It wouldn’t have worked either. The problem is where is so much nitrogen, the essential element for plant growth along with phosphorus and potassium, going to come from? In short, the balance of organic matter in the soil is like a bank account: we balance income and expenditure. If we have been extracting nutrients for years, to replenish them we have to add them again, with the equivalent of increasing the annual production of nitrogen fertilisers by 75%. Where is so much nitrogen going to come from?

Another recipe tells us that we can reduce our carbon footprint by switching from imported to local food consumption. Is transport responsible for most of the footprint? Data from Ourworldindata.org, my go-to site for not coming across as a brother-in-law (Spanish expression meaning to give unsubstantiated opinions)

when giving a food opinion, tells us no. The important thing is not where the food comes from. The important thing is not where the food comes from, but what we eat. It’s not about replacing industrial beef with organic and local beef. It’s about eating less beef and dairy of any kind, whatever your ideological commitment can bear.

Fortunately, the left is more tolerant than the right of being told the truth: that to achieve climate change targets we will have to change the way we consume. What the left does not tolerate so well is being told that to achieve climate change targets we will also have to improve our cognitive biases. One of the fallacies we fall into most easily is the so-called naturalistic one, whereby we think that industrial is bad because it is not natural, and natural is good because…, well, because it is, which is why it is a bias. Our brain has evolved to believe this, we still don’t know why.

Let’s take the example of fishing. All we have to do is put “industrial” agriculture or fishing in an article for the brain to act and think: “bad”. Is artisanal fishing better than industrial fishing? It depends. Local fishing has its ecological advantages: they generate more jobs and they are much more concerned about overfishing, because they can’t go fishing elsewhere. But their carbon footprint is double that of a deep-sea trawler, which emits much less per kg of fish (it also depends on the species fished; lobster uses a lot of fuel and sardines very little). The problem with industrial fishing is the sustainable management of fishing grounds, not its carbon footprint.

Is aquaculture bad because it is industrial? Its carbon footprint is only slightly higher than that of industrial fishing, and much, much lower than that of meat (organic or not). It is an efficient way of producing protein. The important thing is that it doesn’t deforest mangroves.

Umberto Eco said that there are problems that have to be solved by demonstrating that they have no solution. How do you solve a problem without a solution? By doing damage management, because we cannot aspire to more, while we move forward with technical, but also political and personal solutions.

But for this it is important that we are not technophobic. Let’s not blame technology for not having solved an unsolvable problem. Let’s use it to make things better. And before the relevant troll comes out and says that I am paid by Monsanto, I will say that these opinions, in the world of development cooperation, have not exactly helped me to make friends. I do it by vocation.

You may also like

Edward O. Wilson and his diagnosis of humanity in a tweet

This article was published in El País on January 20, 2022. On 26 December, Edward O. Wilson, the bi

SHOULD ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES BE PAID FOR?

Why is it justified to pay people in poor countries to plant trees – although it is better to

Hypocritical chocolate

A few months ago I commented in this post that a Finnish company was promoting lab-grown coffee unde

Post a comment